Description

What does it take to transform an aspiration into reality? Join us in this episode of Impossible • Possible as we dive deep into the remarkable journey of Seth Bernstein, CEO of AllianceBernstein. From his early dreams of becoming an architect to navigating the complex world of capital markets banking, Seth Bernstein’s career is a testament to adaptability and resilience. Reflecting on his New York City upbringing and prestigious education at the University of Pennsylvania and the London School of Economics, he shares insights on the pivotal moment when J.P. Morgan merged with Chase, shifting his path towards managing investments. “Trust is the cornerstone of finance,” he asserts, emphasizing the immense responsibility of safeguarding clients' wealth. Seth Bernstein also addresses the pressing issues of globalization, the aging population, and the critical need for immigration to fuel economic growth. Tune in to discover how mutual trust and competence shape his leadership philosophy at AllianceBernstein.

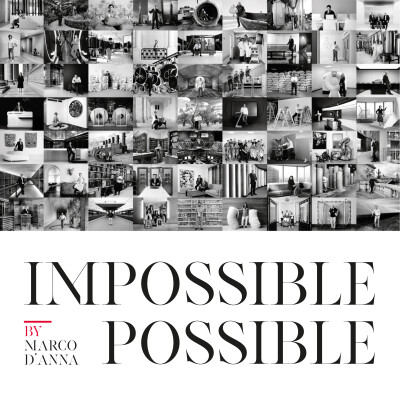

About the podcast Impossible • Possible

For its 160th anniversary, Societe Generale wanted to celebrate the relationship of trust with its clients and partners, without whom nothing would have been possible. Thus, was born the Impossible • Possible art project. Marco D'Anna, a photographer, produced a series of 75 portraits of these men and women on behalf of the Group: entrepreneurs, doctors, financiers, families, volunteers, musicians, industrialists... We decided to go beyond the images... Discover these human stories, where the impossible becomes possible, these authentic testimonials where the protagonists reveal their paths, their visions, their passions.

Hosted on Ausha. See ausha.co/privacy-policy for more information.