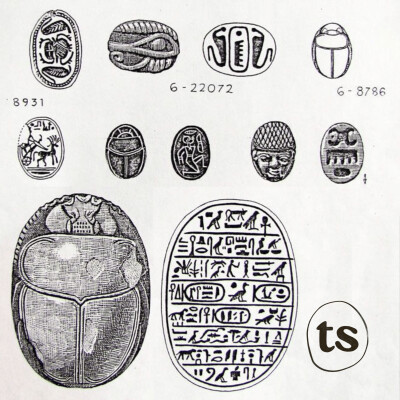

Speaker #0Belgium, early 1990s. Archaeologists dig through layers of earth, clear and dark. What they do not know yet is that, buried in the rock beneath, lies a secret. A tiny beetle-like insect. 298 million years ago, it died near a body of water. Its body sank into mud, into fine sediment. And over millions of years, the sediment hardened into stone. The flesh disappeared, but the earth never forgot its shape. It remained, hundreds of millions of years later. It still belongs to the world. 25 years later, Italy, July 2025. I visit my mother's house, nestled in a nature reserve in Lombardy. As I start my first meditation in the garden, I realise I cannot be at peace. Tiny living beings keep me from serenity. They buzz, they fly, they land on my skin. At first, it feels invasive. One insect crashes into me mid-flight, then vanishes. Who are you? I think, but it's already gone. A couple of days later, walking in my neighbour's garden to pick some fruit, the same insect hits me again. 'It's a female European stag beetle,' my neighbour says, running after her as she lands on a tree. 'Look at her,' he calls as I approach. She's clumsy, but how could she not be? She's huge, flying with two tiny wings and those massive stags. I would be clumsy too. Days later, I swim in the lake. Near the shore, another insect lands on my skin. I look down, amazed. A beautiful metallic green and yellow. It is the green scarab beetle. As I wade deeper, I see some drowning in the water. I gather leaves, lift them up, and bring them to the shore. Moments later, some refuse to leave my skin, as if saving them had bound us together. Another time, as I eat a sweet chocolate gelato, one lands awkwardly on my light pants. I let it stay, and we walked together for a while. Have you ever seen one? Have you seen their green colour? I cannot explain it to you. It looks like the inside of a green Abalone, pearly but metallic at the same time. On their shells, you can see every shade of green that exists on earth. The green scarab holds them all. Weeks later, France, Mediterranean shore, July 2025. I am back from Italy, and I do what I always do when I return home. I go to the sea. On the small paths I know well. Among pine trees, rosemary and lavender, I breathe in the iodine scent I have missed. But when I arrive at the shore, I notice something. Where are the buzzes? I don't hear them anymore. I don't feel insects landing on my skin. And I realise, I don't see scarabs in the cities. I never hear them at home. Suddenly, I feel grief. Something is missing. I am not whole. I feel separated. 2,092 years earlier, Egypt, 68 BC. A woman is burying an object on the Nile banks. Her hands get dark as the black sediment nest under her nails, but she continues untroubled as if she were in a calm trance. From her pouch, she takes a small object, a scarab made of turquoise. She observes it, raises her hand up towards the sun, as if she were discovering it for the first time. But she does not. She just remembers how it looked when her grandmother first offered it to her. It was soft, as a baby's skin. Now some yellow, encrusted lines appear, as the sand beneath her feet during the dry season. She remembers what her grandmother said, 'This scarab accompanies the souls of the ones who open their eyes until they close them and beyond. It gives life, makes all fertile, like a seed in the earth.' The woman delicately places the scarab in the hole she dug, like a seed in the womb, she thinks. If you can give life to earth, you can give life to me. Oh Isis, how I wish to be a mother. And as she covers the scarab with the black sand, she whispers something so low that you could think she did not say those words. The scarab did. The sand, the Nile, or the date palms around. The voice said, 'And when I will be buried in the soil, like my ancestors are. It will help give life to what happens next, until I close my eyes and beyond.' 2070 years later, French Alps, July 2003. I am six years old, lying on a field among the haystacks. A big beetle is making its way among the herbs and flowers. I am curious, but scared. 'Don't touch scarabs. They stick on your skin until it's impossible for you to let go of them,' my grandparents once told me. So I grab one dry herb and gently touch it with it. Its black skin is almost blue. It reflects the sun so much it looks like it holds it within. But the scarab stops moving. And it feels so light now. Its legs retracted. Is it dead? Did I kill it? I slowly push myself back. No, you cannot be dead, I think. I push it again with the herb, but it doesn't respond. It is indeed dead. I feel sad and ashamed. I look around. My cousin is playing with the dogs as if nothing happened. But the scarab just died, and we should all feel sad about it. I want to grieve, but suddenly I hear a loud buzz. I look back at the scarab, and it just flies away, as if nothing had ever happened. You fooled me. It fooled me. 22 years later, Sardinia, Italy, May 2025. 'Beth, look,' I say. 'Look at that scarab!' Unfolding before our eyes on a flowery, earthy path leading to the Mediterranean Sea, a scarab, black as the night sky, is rolling head down a big ball, three times its size. We stay there, observing it. It changes direction. Goes up and down, starts again, but never fails. We want to understand. Back home, we check on the internet. Beetles find dung to lay eggs in or to bring food to their family. They are among the strongest insects. They create these big balls of dung and carry them to an underground chamber. From it, life will rise and emerge. 5,000 to 3,000 years ago, the ancient Egyptians witnessed the same thing my friend and I did. For them, this was sacred. It was interpreted as a symbol of the cycle of life, death and rebirth. From this, they created the god Khepri, a scarab-headed god. He was the sunrise god. One myth said that Khepri pushed the sun across the sky and that every night it would push it down into the underworld, only for it to rise again each morning, like the scarab with the dung balls. The word Kheper means 'to emerge' or 'to come into being'. For the ancient Egyptians, this also symbolised the resurrection of the body, which they understood to be similar to the way new scarab beetles emerge from inert matter. The regenerative powers of these scarabs could be used by the living or the dead for healing and protection, whether in daily life or during a person's journey into the afterlife. They crafted figurines and amulets from them, holding some close to their hearts. One month later, back in France, Mediterranean shore, July 2025. As I walk along the promenade to get back home, it is dusk. I imagine what it would be like without the silent noise of the city, the quiet of insects, of living things, and without the hum of cars, the alarms, the engines. Would I hear you? Or are you not here anymore? Where are you? We build cities that completely separate us from life, from living beings, as if we could live without them. It's not only about the connection I've created with them, but also about how they are part of an ecosystem and serve the whole of it. Scarabs are decomposers, they are pollinators, they are food sources to birds and mammals, they prey on tiny insects which affect plantations, they are part of the earth, just as we are. As I walk, I notice fruit trees planted in a place I never pass. I am surprised by the view, pomegranates and fig trees. Such a symbol, I think, of life and wisdom. You are here, as my ancestors walked past you in places I had never seen. I do now. Even if you are surrounded by cement, You're still breathing the same air as me. And as I look at them, a tiny bee lands on one of the leaves. You're not a scarab, I think. But with you, little friend, I realise that nature is never too far. It's our role to notice you, to give you space and life. Now, I don't suggest we start worshipping beetles or the god Khepri. But let's rethink how we see things. Our ancestors deeply revered natural processes, not only for their beauty and mystery, but for how much they explain life and humanity. They help make sense of things and bring us back to our place among an ecosystem, among other living beings that are truly magical. I mean, if you look at a green beetle, doesn't it hold the mystery and beauty of life? I hope one day a stag beetle runs into you in its clumsy way, or you see a beetle roll a dung bowl, or meet a green beetle on a lake, and that you'll make friends with them. And remember, they were here long before us. They met our ancestors, the trees around your household. Perhaps they once landed on them and were cherished. They know us more than we know them. And maybe they will know our future generations, walking among us until we end or until we thrive. If we end, they will have met us, made friends with us. If we thrive, perhaps someone will hold a beetle in their pocket. A blue one, found in a market. One that once belonged to Egypt. They may not know what it was used for. But we do now, and we know it holds grief, hope, life, and death. It holds the world. Thank you for listening to this podcast episode. It was quite different from the others, but I really loved how this one felt like travelling through time, places and worldviews, merging them into one. This was really to show that they are not separate. They still live as footprints on the earth, as genes inside you, as memories. Nothing is too far from us. I really hope it resonated with you. If it did, please share it with those around you and rate this podcast five stars on Spotify or Apple Podcasts. You can also leave a comment on the episode on Spotify. I'd be really happy to hear your reflections. I'm curious to know which part spoke to you most in this episode. So don't hesitate to share that too. I wish you a beautiful day or evening, and I'll talk to you soon.