- Speaker #0

Welcome back to the Deep Dive.

- Speaker #1

Today we're stepping away from broader themes and digging into something really specific, really personal. We've got our hands on court transcripts from 16th century Geneva. These are from the Registre du Consistoire de Genève. And our mission isn't about high theology today. It's about seeing how the strict moral oversight of the Reformation played out right inside people's homes. You know, when you think of Calvin's Geneva, maybe you picture debates about doctrine, but this powerful court of ministers and elders They were just as worried about whether you were, well, doing your chores or fulfilling your marital duties. And this whole deep dive revolves around one incredibly intense, years-long marital fight between a hatter named Jean Cugnard and Estienne Acostel, an innkeeper's daughter. And the entire conflict, it boils down to the failure, the physical failure of one basic conjugal duty.

- Speaker #0

Exactly. And what makes this case just fascinating, I think, and so useful for us... is that you see this sort of iron will of the Reformation, this demand for order and conformity smashing right up against a really messy private anatomical problem. It's amazing how this one single case file shines a light on 16th century marriage law, the pretty strange state of medical knowledge back then, and it even pulls in John Calvin himself to weigh in on divorce. Okay, let's really unpack this collision between spiritual law and the physical body. Where does it start?

- Speaker #1

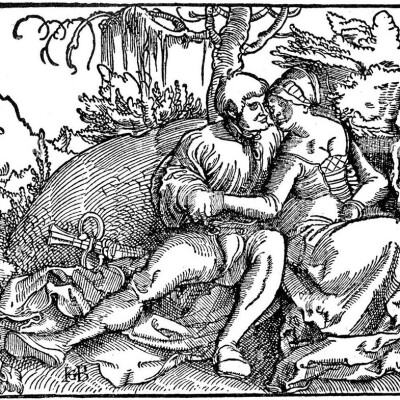

Right, so the story kicks off in July 1562. The husband, Jean Cunard, goes straight to the consistory. He wants a separation. He paints this picture of Estiana being totally rebellious, disobedient, contrary, won't sleep in the same bed, and specifically refuses what the court calls the devoir de femme, the wife's duty. He's claiming complete non-consummation. And we get these little glimpses into just how bad things were at home. Estiana actually admitted throwing out some meat he bought. Her defense was full of vermin.

- Speaker #0

Right. But the consistory zeroes in on the main issue, the lack of consummation. She admitted it. They hadn't had sa compagnie, his company, meaning intercourse. And at this stage, you see, the consistory treats it purely as her fault, a moral failing, a kind of rebellion against the natural order. Marriage was absolutely fundamental to civic life, spiritual life in Geneva. Estienne was seen as shaking that foundation.

- Speaker #1

So what did they do? Tell her off.

- Speaker #0

Oh, much more than that. The reaction was swift and pretty uncompromising. They ordered her flat out to perform her duty de jour et de nuit, day and night.

- Speaker #1

Day and night, wow.

- Speaker #0

Yes, under threat of punishment, Chastier. And they weren't bluffing. When she still refused, they took away her right to communion, the Seine, and then they recommended something really extreme.

- Speaker #1

Okay, what?

- Speaker #0

That she be put in a croton. Now, nobody's entirely sure what a croton was, but it sounds like a particularly nasty, deep, dark kind of prison cell.

- Speaker #1

They wanted to put her in a dungeon to scare her into sleeping with her husband.

- Speaker #0

That was the explicit goal. The record says it was to induce her a rendre de voix de femme envers son Mary, to make her render her wifely duty to her husband. It sounds brutal to us, but it shows just how seriously they took marital compliance.

- Speaker #1

That's chilling. So the pressure is intense. What happens next? Does she give in?

- Speaker #0

Well, this is where the story takes a sharp turn. Estienne gets hauled before the council itself. And her story changes completely.

- Speaker #1

How so?

- Speaker #0

It's no longer about rebellion or disobedience. Now it's about impossibility. She says, look, she's willing to go back to him, but she's simply incapable of having sa compagnie. She physically cannot have intercourse with him.

- Speaker #1

Ah, so it shifts from won't to can't.

- Speaker #0

Exactly. And her mother actually backs this up. She testifies that she'd already taken Estienne to see a local expert, a barbier ou suite chirurgien, a barber or a surgeon, to figure out the problem.

- Speaker #1

And what did the surgeon say?

- Speaker #0

Nothing helpful. The mother reported that he needs shuranko and rest. He basically knew nothing, couldn't figure it out.

- Speaker #1

Why not? Didn't they understand basic anatomy?

- Speaker #0

Well, that's the crux of it. You have to remember, 16th century medicine and law. For female impotence, impotentia coiandi, the traditional legal category under canon law wasn't about desire or anything psychological. It was physical, usually diagnosed as arctitudo.

- Speaker #1

Arctitudo.

- Speaker #0

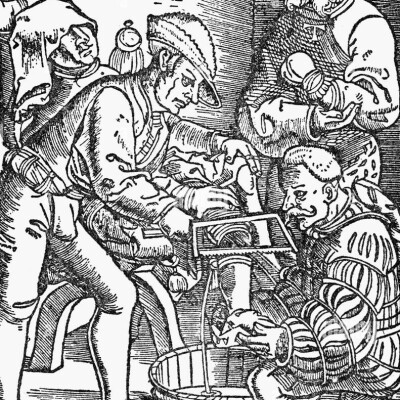

Yeah, it means extreme narrowness or tightness of the vagina. A physical blockage that prevents intercourse and, crucially, prevents generation having children. That was the key concern. But diagnosing it was tough. Surgery was often seen as a kind of low-status craft then. And a lot of the university-trained physicians, they were still working off ideas from ancient Greece, like Galen's one-sex model.

- Speaker #1

One-sex model.

- Speaker #0

Yeah, the idea that female organs were just sort of inverted, imperfect versions of male ones. So understanding unique female anatomy, it lagged way behind. If all you can imagine is a blockage like Octitudo and you don't have the tools or maybe even the willingness to properly examine, well, the local guy comes up empty.

- Speaker #1

OK, so a legal problem hinging on a medical mystery that the local surgeon couldn't solve. How did they move forward?

- Speaker #0

The breakthrough comes right at the end of 1562, December 31st. The syndic, a chief magistrate, reports that Estiana has been examined again, but this time by Sage's fam.

- Speaker #1

Midwives.

- Speaker #0

Exactly. And midwives, you see, often had much more practical hands-on experience with female bodies than many male surgeons or academic physicians.

- Speaker #1

And what did the midwives find?

- Speaker #0

This changed everything. Their report was clear. She was fort estroite et comme inabile, very narrow and sort of unfit for intercourse.

- Speaker #1

They gave specifics.

- Speaker #0

They did. They noted she couldn't even tolerate the insertion of a petitouet, a small finger.

- Speaker #1

Wow, that's pretty definitive physical evidence.

- Speaker #0

Absolutely. And that concrete proof, it instantly shifts the whole case. It's not about moral failure anymore. It's about anatomy failing the requirements of the marriage contract. This becomes a canonical issue.

- Speaker #1

So what does the council do with this finding?

- Speaker #0

They go straight to the top. They consult the main man in Geneva, Jean Calvin himself.

- Speaker #1

Right, the ultimate authority. What did Calvin say when he heard the midwives report?

- Speaker #0

Calvin's response was direct and cut right to the heart of the Reformation view of marriage. He declared, and I'm quoting the essence here, Meaning? Meaning, basically, if the husband and wife cannot have physical company together, if they can't consummate the marriage, then it is not a marriage. It has to be declared null, void, end of story. For Calvin, consummation was absolutely central.

- Speaker #1

Okay. So Calvin rules, annulled the marriage, problem solved.

- Speaker #0

You would absolutely think so. Clear ruling from the top authority based on physical proof. But this is where the story takes another, frankly, quite startling turn.

- Speaker #1

What happened?

- Speaker #0

Instead of just processing the annulment, the council, well, they hesitated and they proposed something else entirely, something radical.

- Speaker #1

Which was?

- Speaker #0

They suggested consulting more experts, medicines, doctors and surgeons to see if, and get this, if there was a way to give Estienne an autorefuture que celle de nature.

- Speaker #1

Another opening than that of nature. They mean surgically.

- Speaker #0

Yes. They suggested it could be done artificioman. They were seriously proposing surgery to essentially reconstruct or enlarge her vagina to make intercourse possible.

- Speaker #1

Wait, surgery in the 1560s? For that? That sounds incredibly dangerous. Borderline experimental.

- Speaker #0

Oh, absolutely extraordinary for the time. Surgery was brutal. No effective anesthesia. Infection was almost guaranteed. The risks were immense, especially for anything internal or intimate. Anatomical knowledge was patchy, and there were huge taboos around female genitalia. You even see censorship in anatomy books from the era. So the idea of doing this kind of, well, early plastic surgery on the vagina to fix Arctitudo, it was incredibly daring. You had surgeons like Ambrose Perret around then who believed surgery should repair the defects of nature. But this, this was... pushing that idea to an extreme, highly risky place.

- Speaker #1

So why? Why even float this incredibly dangerous idea when Calvin had already given them the hour to annul the marriage?

- Speaker #0

That is the million dollar question, isn't it? It suggests there was this immense pressure, maybe from the council itself, to preserve the marriage contract at almost any cost. That social pillar, that civic building block seems so important that they'd contemplate radical, life-threatening intervention rather than just dissolve it.

- Speaker #1

It seems like the ideal of the unbreakable marriage contract almost trumps the actual physical reality and even Calvin's theological ruling.

- Speaker #0

It certainly looks that way. The drive to fix the body to fit the contract rather than voiding the contract because the body couldn't comply. The social order seemed desperate for a physical fix, even a risky one.

- Speaker #1

So did they actually try to find surgeons? Did this proceed?

- Speaker #0

No. And the person who stopped it wasn't a doctor worried about the risks. or a minister citing Calvin, it was the husband, Jean Cugnard.

- Speaker #1

Cugnard refused, after all his complaints.

- Speaker #0

He flat out refused. In March 1563, the council ordered him to take Estiana to the surgeons, and he refused to comply.

- Speaker #1

Why? What was his reason?

- Speaker #0

His reason tells you so much about gender, shame, and the idea of a wife back then. He said quite clearly, Il ne voudra pas une femme qui aura estimé par les chéroviens et barbiers.

- Speaker #1

He wouldn't want a wife who had been... Handled by surgeons and barbers.

- Speaker #0

Exactly. Mainy handled, manipulated the very idea of male surgeons examining and altering his wife's intimate anatomy, even to potentially fix the marriage. It destroyed her value, her purity in his eyes.

- Speaker #1

So his sense of propriety or maybe ownership over her body was stronger than his desire to have the marriage consummated or validated?

- Speaker #0

It seems so. That notion of the untouched, unmanipulated female body, at least by those hands, trumped everything else, the consistory's pressure, the council's order, maybe even his own initial demands. It's a real window into the mindset of the time.

- Speaker #1

So what happened to them in the end? With the surgery off the table, did they finally get the annulment Calvin recommended?

- Speaker #0

Well, like a lot of these historical deep dives, the ending isn't perfectly neat. The surgical idea dies, but the marriage doesn't immediately dissolve either. The consistory records show the case just kind of drags on through 1564. It actually reversed back to the earlier kinds of complaints, accusations of domestic strife, Cugnard hitting her, Estiana calling him a Lauren, a thief, standard marital misery almost.

- Speaker #1

So they didn't separate or annul.

- Speaker #0

We know they were eventually readmitted to communion. which suggests some kind of reconciliation or at least a truce enforced by the consistory. But whether the marriage was ever formally declared null, as Calvin advised, or if they just remained legally bound but miserable and probably separate, the records we have just don't give us that final definitive answer. It kind of fizzles out.

- Speaker #1

Wow. What a story. So stepping back, what are the big takeaways from Estiana Costell's case?

- Speaker #0

I think it's this incredible snapshot of a moment where everything collided. You have this strict spiritual law from Calvin. saying non-consummation voids the marriage. You have the physical evidence from the midwives confirming the impossibility. And yet you have this powerful social and institutional pressure pushing for a physical, even surgical fix. It really highlights how, for the Reformation state in Geneva, the body's performance, especially sexual performance within marriage, was tied directly to civic order and spiritual compliance.

- Speaker #1

Yeah, it starkly reveals the immense pressure on women back then to basically be sexually functional, according to a very narrow definition. And the extreme measures considered when a woman's body physically couldn't meet that standard.

- Speaker #0

Absolutely. The fact that they even contemplated such a dangerous novel surgery speaks volumes about the desperation to uphold the marriage contract.

- Speaker #1

So any final thought for us to chew on from this?

- Speaker #0

Yeah, here's something interesting to consider. In 1563, Estiana's problem, Arctitudo, was seen as purely physical. anatomical, a mechanical flaw that theoretically you might even be able to surgically repair, however risky. But fast forward a couple hundred years, medical thinking shifts dramatically. When doctors encounter non-consummation, the focus moves away from just the physical narrowness. It starts to become about the woman's mind, her desire, or lack thereof. It morphs into ideas about the soul, the moral dimension, and eventually lands on diagnoses like frigidity.

- Speaker #1

Ah, so from a potentially fixable physical defect to a psychological or moral failing.

- Speaker #0

Exactly. So maybe Estiena's case, with its proposed surgical fix, represents one of the last moments where this kind of female sexual incapacity was viewed almost entirely as an anatomical engineering problem, right before the medical world started classifying it very differently as a problem of will or desire or character. It's a fascinating pivot point.